The president of Ghana, H.E. John Dramani Mahama, signed the Ghana Gold Board (Goldbod) Bill into law on April 2, 2025. This new legislation seeks to regulate the country’s gold supply chain, particularly gold sourced from the artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) sector. The supply chain of large-scale gold and mining activities in general are still largely regulated by a separate state regulator—the national Minerals Commission (MinComm).

Goldbod is an offshoot of a state enterprise called Precious Minerals Marketing Company (PMMC), which previously served as the National Assayer, charged with assaying ASM gold before exports.

Upon its establishment, the GOLDBOD will also have the exclusive legal right as the sole assayer, seller and exporter of gold purchased from the small-scale gold.

Dr. Cassiel Ato Baah Forson

(Finance Minister, Ghana)

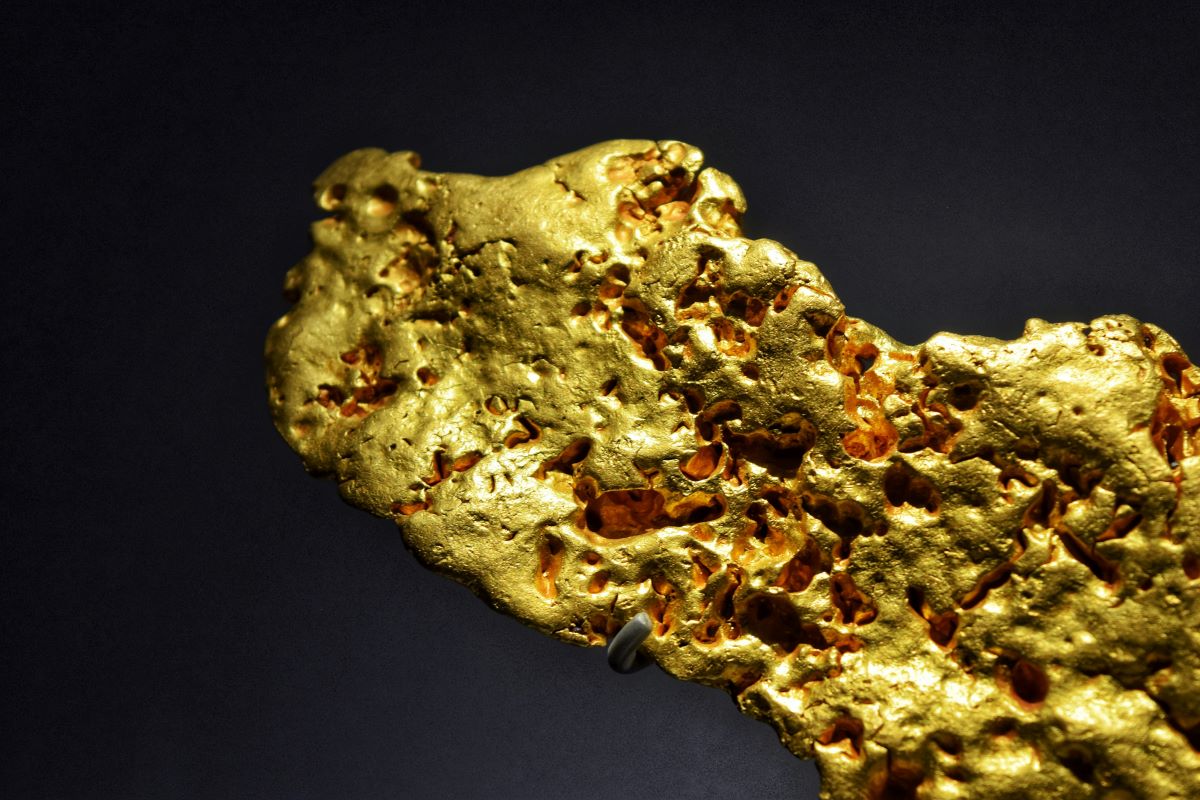

Ghana is currently Africa’s number one supplier of Gold and the world’s number six.

Over 50% of gold mining in the West African nation is managed by local subsidiaries of international mining conglomerates such as Newmont Corporation (USA), AngloGold Ashanti (South Africa), Gold Fields Ltd (South Africa), and more recently, Shandong Gold Mining Co. (China).

In 2000, ASM contributed just 10% to Ghana’s total mining output. By 2024, the contribution of ASM had expanded to a third of the nation’s mining output, according to official records. Government sources believe ASM gold would rival large-scale gold if smuggled gold were properly accounted for.

Some industry experts have expressed concern over the possible overlap of regulatory mandates between MinComm and the newly formed Goldbod. Goldbod leadership has since tried to offer clarity by emphasizing that Goldbod’s mandate focuses on regulating and streamlining the supply flow of gold mined specifically from the ASM sector.

Others have argued that the more immediate challenge is the inability of the MinComm to properly enforce mining laws on ASM operators to ensure maximum environmental protection. As such, they believe the mandate of the Goldbod should reflect this priority area. The part of the Ghana Gold Board Act that addresses ASM operations directly is in the area of providing support services to ASM operators

A major cause of this problem is the number of licensed artisanal and small-scale miners across the country. They number in the thousands. Consequently, the state enforcement apparatus lacks the capacity to properly monitor and enforce mining regulations across the vast number of licensees. It appears, political and business interests have outweighed the prudence of keeping the rate of license issuance in step with enforcement capacity.

To provide perspective on the dizzying pace of mining licence issuance by the national regulator, specifically, the Minerals Commission:

It is interesting to note that, out of the over 2000 licences issued, large-scale mining licences make up less than 20. Not 20 percent, but 20 licenses.

Evidently, the Minerals Commission is overwhelmed. It appears the establishment of the Goldbod does nothing to address this very pressing challenge. Instead, the Goldbod is mandated to address an entirely different problem—ASM supply chain discrepancies.

There are a few broad statements about providing support to small-scale mining companies captured in the new Goldbod legislation, though the operationalization of this is still unclear. Neither is it clear how providing support to small-scale mining entities would contribute to ensuring compliance with mining laws. Unless the incentives provided outway the profitability associated with smuggling, more effort would be required to ensure compliance.

It does not take a rocket scientist or an industry expert to recognize that, the establishment of Ghana Gold Board is more of a reactionary, almost panic-driven solution to depleting foreign currency reserves and a weak currency than it is the product of creative genius by a visionary government. Is this altogether malevolent or wrong? Not necessarily. Desperate times call for desperate measures. But of course, the government cannot present this reality as its driving motivation for commandeering the local ASGM market. It must bring hope and garner public goodwill. This stark reality must therefore be carefully draped within a more palatable objective: Injecting some sanity into a chaotic ASM sector, for instance. A worthy goal indeed, whose realization need not be mutually exclusive to the primary objective.

First of all, on the matter of reactionary and panic-driven solutions: Ghana is currently locked out of the international bond markets, which have hitherto served as a reliable source of foreign currency till the immediate past government milked the heck out of that cow till it got sick and died, at least for Ghana it did. The current government anticipates that the volume of foreign currency injection by an inherited IMF program would not solve all our foreign reserve needs, and rightly so.

A positive balance of trade year-on-year, coupled consistent, high-volume foreign currency repatriation, are deliverables the ASGM sector can afford. But of course, the large-scale gold sector is pretty much untouchable as it is. Unless the government does not mind being cancelled on the square of international gun-bolt diplomacy by the home governments of these conglomerates, plus having to deal with an avalanche of lawsuits in foreign jurisdictions, it would not meddle with prevailing arrangements with large-scale players. ASM however is that little kid on the block who can be bullied into giving up his candy without much of a fight—at least per the government’s estimation. Hence, the Goldbod and its strategically narrow target.

And on the matter of Goldbod not being visionary: The only thing visionary about Goldbod is its name—Goldbod. But then again, we have Cocobod. So no, not even the name. There is something Goldbod bears more semblance to than Cocobod (Ghana Cocoa Board). The Gold for Oil (G4O) project. The broader and more accurate term is the Domestic Gold Purchasing Program (DGPP).

This was a program implemented by the immediate past government, during which they empowered the state, specifically the Bank of Ghana (BoG), with the right of pre-emption on all gold mined from the ASM sector. The BoG went on to procure as much gold as it could get using proxy traders, including the PMMC, and exchanged the same for dollars and for oil. It was quite brilliant, though not as novel or as ground-breaking as was touted.

The downside was that the overall strategy seemed to prioritize maximizing dollar repatriation over prudent accountability. As a result, a lot of money seeped through the cracks, which ultimately led to some huge losses. Nonetheless, dollars were the prize, and dollars they got. So much so that the government left behind a good amount in the nation’s foreign reserves, which they later boasted about quite a lot. Another downside, of course, was that the BoG and its proxies practically kicked licensed private bullion industry players out of the market.

In fact, they went as far as to revoke export licenses. The fact that there has been no significant pushback from industry players to date remains a shocker. But clearly, this government took a cue from the successes of the DGPP; borrowing quite copiously from that playbook, though I suppose they would at least attempt to avoid the sort of losses that riddled the previous program, and perhaps be innovative and make more out of it.

[The gold market is] fragmented, uncoordinated, and unregulated… to address these issues, the Ghana GoldBod will be mandated to regulate and streamline the sector.

Dr. Cassiel Ato Baah Forson

(Finance Minister, Ghana)

One thing is for sure, the current government believes it can implement the Goldbod’s purchasing program with much more style, gusto, and tact than the former administration. It is no wonder they began by establishing the legitimacy of the relevant institution, ie, the Ghana Gold Board Act 2025. A legislation that, in effect, establishes a state monopoly, imbuing it with the powers of a regulator and of an enterprise. Again, why no one has yet challenged this structure in the law courts is a mystery. Moreover, the Goldbod does not just double as a player, but is the sole player.

The irony is that Goldbod also has the power to issue licences in those same areas in which it has been declared the sole player. The intention therefore is that, just as with the DGPP, Goldbod would carry out its player-related mandates through proxies, ie, Goldbod-licensed private bullion operators. One would wonder what rationale lies behind declaring a state entity as the sole player in a sub-sector, then turning around and delegating the functions of that role to potential private competitors.

The Goldbod shall issue licences to persons engaged in a business or related activity in the gold trading and marketing industry or an ancillary business or related activity.

Goldbod Act, 2025

There is more. Goldbod also has the power to determine the prices of ASM gold across the entire local market, from miners to retailers, including at what exchange rate to transact trade. An active player in the market, specifically, the buyer, the sole buyer, also determines at what price the product is sold on the market because the same entity doubles as a regulator. Talk of total market domination!

It would appear that the goal is to assign to the Goldbod all the power, all the privileges, but almost none of the responsibility. Why? The most capital-intensive, most standard-driven, most energy-exacting levels of the gold value chain are in gold exploration, extraction, and processing. Not to mention the level of risk and the time it takes to execute these phases properly and profitably. Trade and export are less exacting across almost all the metrics stated. Would this overall strategy of targeting the low-hanging fruit in the gold sector work? If the local gold traders are somehow motivated to be loyal, compliant pawns of this all-powerful state monopoly, by all means. Hopefully, the details of operationalization would ensure a significant level of benefit for gold traders as an incentive for compliance, and eventually for miners as well.

Compliance is often a by-product of policies that enable businesses to thrive, coupled with efficient enforcement measures. Businesses are motivated primarily by profitability. Goldbod does not have to run losses like the DGPP did. But, it can keep its profits minimal as a strategy to court maximum buy-in and cooperation from private industry players. This can be achieved by keeping the (state-determined) local prices, taxes, royalties, and possible exchange rate-related losses at reasonable levels. After all, maximum dollar repatriation is the primary objective. Let us face it, Goldbod needs the buy-in of these businesses to maximize gold procurement. Pursuing high-handed tactics with miners with the intent to circumvent gold traders, or creating state cabals with selected gold traders to the detriment of others, might work. But only in the short term.

The question is, would the Goldbod choose to sacrifice profitability for compliance, or compliance for profitability? It is like a horizontal scale with an adjustable slider. This is indeed a zero-sum scenario.

There are two primary strategies to court cooperation from the private sector in implementing radical policy changes. Goodwill, transparency, and mutual respect, on one hand; high-handedness, manipulation, and one-upmanship, on the other hand. If the leadership of Goldbod ignores the prevailing realities in the process of operationalizing its mandate in favour of profit maximization, cronyism, or over-confidence disguised as political will, the outcome is almost predictable. A lot of the existing local traders would do what entrepreneurs are wired to do—find innovative ways to solve business challenges.