Introduction

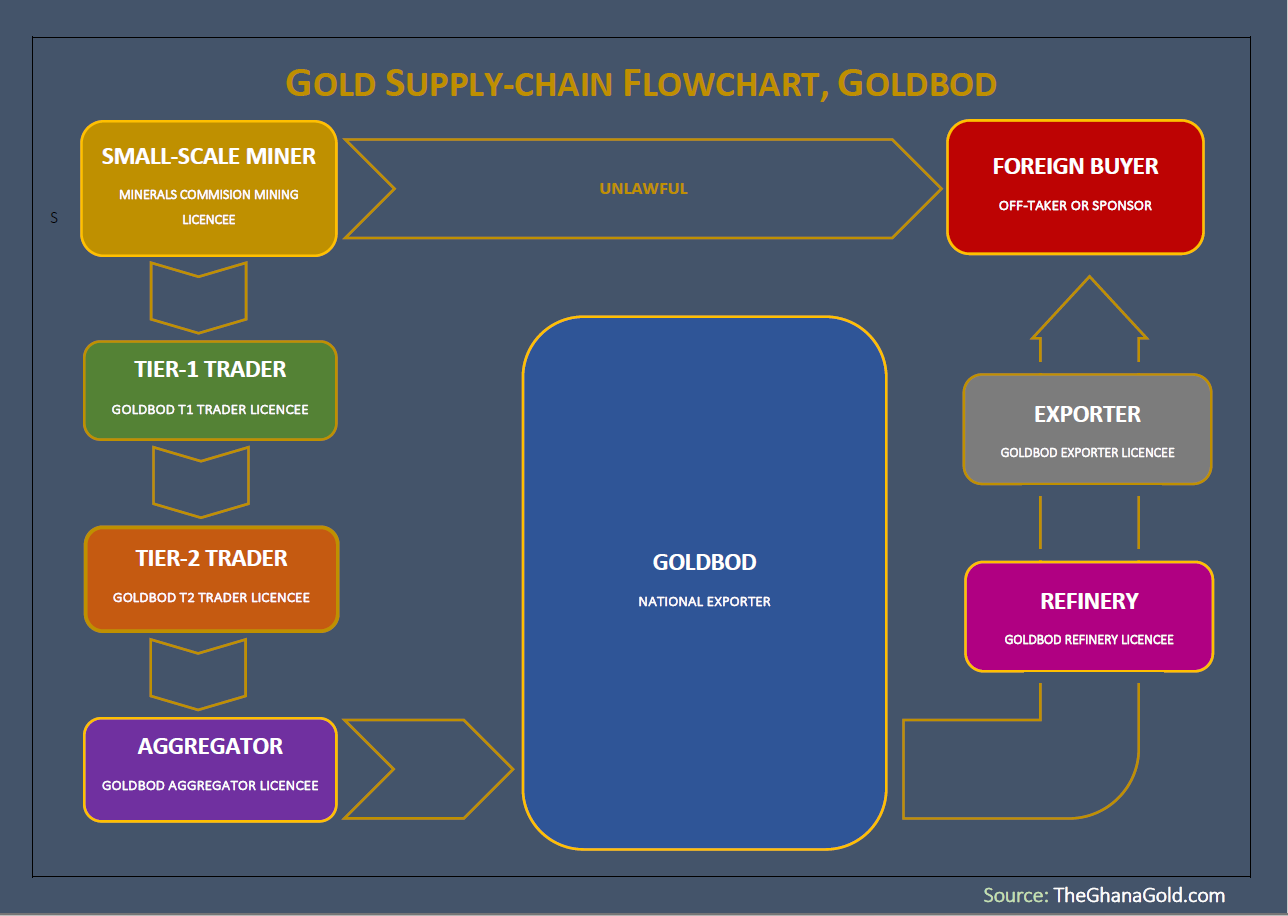

In Gold Supply Flowchart: Part 1—Before Goldbod, we run through the gold supply structure that prevailed prior to establishing the Ghana Gold Board. The structure of the local gold supply chain, as previously detailed, evolved over time. However, the political disruptions occurred between 2022 and 2024. The Ghana Gold Board Act (Act 1140) was passed by the new government on April 2, 2025. This marked the dawn of a new era in the local artisanal and small-scale gold mining market.

The new government announced that it intended to sanitize the ASGM sector of smugglers, streamline the entire sub-sector, and maximize national benefit from gold exports. In pursuit of these objectives, several notable policy changes were introduced under this new regime. Let us go through the most pivotal ones:

1. Consolidation of Authority

The mandates, functions, and authority of several state institutions were incorporated into the Ghana Gold Board, giving it vast powers and an extensive mandate in Ghana’s gold industry. Some of the institutions whose mandates the Goldbod either borrowed or took over are: Precious Mineral Marketing Company, Minerals Commission, Bank of Ghana, the Judiciary, and the Ghana Police Service.

Precious Mineral Marketing Company

The Precious Minerals Marketing Company (PMMC) was the predecessor of the newly established Ghana Gold Board (Goldbod). The PMMC was a state enterprise that engaged in; assaying, trading, and exporting gold for profit. At a point in its history, the PMMC competed with private sector businesses as one of the many traders in the local gold market.

At the time of introducing the Gold Board Act, the official role of the PMMC was the National Assayer. This mandate empowered the PMMC to assay all gold exports and charge a fee for that service — specifically, 0.2524% of the value of the gold being exported. The National Assayer was also mandated to collect other taxes, including export taxes, on behalf of the state.

That apart, the PMMC was also engaged in local gold purchasing on behalf of the Bank of Ghana, in partnership with selected private sector gold traders between 2022 and 2024. This mandate was activated under the Domestic Gold Purchasing Program (DGPP), popularly referred to as Gold for Oil (G4O), which was introduced by the immediate past government in mid-2022.

Domestic Gold Purchasing Program

Before the DGPP was introduced, the PMMC had not been an active gold trader for some time. In 2016, the Bank of Ghana (BoG) revoked PMMC’s gold trading rights after it had recorded billions of United States Dollars in gold trade-related losses. Interestingly, the losses and the resulting revocation of PMMC’s gold trading rights occurred only a few months after the BoG had designated PMMC as the sole exporter of gold in the country.

It is important to know that the authority of the Bank of Ghana to issue trading licences is backed by law, specifically, the Bank of Ghana Act (Act 612), 2002. Section 50(d) of this Act empowered the BoG to “import, export, refine, hold, sell, transfer or otherwise deal in gold, gold coins and bullion, silver, platinum and any other precious metals as determined by the Board”. By this provision, the BoG could regulate transactions involving precious minerals and license third parties to carry out its mandates in the gold industry.

Over time, the responsibility of issuing gold trading (or dealers) licenses shifted from BoG to PMMC, which was not amiss, since the existing Precious Minerals Marketing Corporation Law (PNDC Law 219), 1989 also authorized the PMMC to grade, assay, value, process, buy and sell precious minerals, as well as to license its agents. It is also important to mention another important gold industry regulator — the national Minerals Commission (MinComm). The mandate of the Minerals Commission (MinComm) however is focused on regulating the extractive sector, ie, prospecting, exploration, and mining, as well as issuing related rights and permits. In addition to this mandate, the Minerals and Mining Act, (Act 703), 2006 empowered MinComm to grant gold export licenses.

Jewellers’ Licensing under Cap 24

In Ghana, the licensing of jewellers historically falls under an outdated law from the early 20th century known as Cap 24 — specifically the Criminal Code (Amendment) Ordinance. This law empowers the Ghana Police Service – CID Department to issue goldsmith and jeweller licences, originally aimed at regulating the handling and trading of precious metals to prevent theft and illicit activities. Though this law was enacted during the colonial Gold Coast period and retained post-independence, it remained valid as no subsequent law clearly stated that it had been repealed or replaced. Till mid-2025, jewelers and goldsmiths continued to receive their operating licenses from the CID Department of the Ghana Police Service.

The Ghana Gold Board

The Gold Board Act has shifted the mandate of issuing export licenses from MinComm to Goldbod. Also, all the mandates, responsibilities, assets, and liabilities of PMMC have been inherited by Goldbod, since Goldbod is an offshoot of PMMC. The history of the PMMC cannot be divorced from the Goldbod, notwithstanding the change in name, leadership, and parent law.

Also, additional powers, mandates, and structures have been added to the Goldbod which did not exist in PMMC. For example, the establishment of the Goldbod tribunal, imbued with authority equal to a high court, and mandated to adjudicate matters within the scope of Goldbod’s functions.

2. State Monopoly of the Local Gold Trade Industry

The Ghana Gold Board Act (Act 1140), 2025 imbues the Goldbod with the “sole authority to grade, assay, weigh, value, purchase, sell and export gold” produced by artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) companies in Ghana. The mandate extends to having the right of pre-emption over “a portion or all of the gold produced by large-scale mining companies”.

These exclusive rights accorded to Goldbod trigger memories from 2016 when the Bank of Ghana declared PMMC the sole buyer of ASM gold. No need to re-echo how that ended. To be fair, past experience does not guarantee future results. It would therefore be improper to assume that the operationalization of Goldbod’s exclusive rights would yield similar results as we saw in the past. The difference in leadership, strategy, and overall competence may well lead to an entirely different outcome. Time will tell.

The list of licenses issuable by the Goldbod suggests that the institution’s mandate also covers storage, transportation, refining, and fabrication (jewelry-making) of ASM gold. Whether these areas are also part of its exclusive mandate is unclear, since these were not categorically listed among Goldbod’s exclusive mandates. However, licenses corresponding with these activities have been listed in the Ghana Gold Board Act as licences issuable by Goldbod.

The framers of the Goldbod Act did not see the need to confer exclusive right status on the latter Goldbod functions. They simply provide that, all relevant agencies and entities are required to obtain licenses from these state authorities or regulators, and operate only within the framework of the licenses obtained.

It is significantly different when the law grants a given state entity the exclusive authority to operate in an industry. Then turns around and imbues the same entity with the power to license private agencies to carry out those same activities. The only other state institution in Ghana that has a similar legal framework is the Ghana Cocoa Board (Cocobod). Presumably, this similarity is no coincidence, given the similarity in nomenclature.

Whether or not there is a practical difference in the operationalization, efficiency, or command of these two types of approaches is a matter that bears future examination. Nevertheless, this write-up is not intended to prove the efficiency or viability of the Goldbod approach. Rather, the intention is to lay bare the facts so that the reader can make an informed judgement.

3. An Expanded Licensing Regime

Precious Metals Marketing Company (PMMC), the predecessor of Goldbod, was mandated to issue exactly one licence at the time the Ghana Gold Board Act was passed. That is the gold trader (or dealers) licence. This licence was required by all agents or agencies who desired to participate directly in Ghana’s local gold trade industry. The new Act gives the Goldbod the responsibility of issuing a total of ten (10) licenses.

This is the list of the licenses issuable by the Goldbod:

- Aggregation License

- Buying License

- Refining License

- Export Partnership License

- Storage License

- Importation License

- Transhipment License

- Transportation License

- Smelting License

- Fabrication License

Exactly two weeks after the Gold Board Act was passed, the Goldbod opened applications for two of the ten licenses—the Aggregator Licence and the Buyer License. Details on the two licenses, including operational, financial, governance, and legal requirements, were made available to the public, including an online application portal. Goldbod announced that six out of the remaining eight licenses would be open for applications from July, 2025. Unfortunately, the scope and requirements of these six licenses have not been made available. Neither is there any information on the remaining two licenses, ie, the Export Partnership License and the Transhipment License.

There are two types of Aggregator Licenses the Goldbod would be issuing— the Aggregator License, and the Self-financing Aggregator License; and two types of Buyer Licenses— Tier 1 Buyer License, and Tier 2 Buyer License.

The increase in the number of licenses issued by the Goldbod’s is a result of several factors. The PMMC-issued gold trader (or dealer) license was separated into the Aggregator Licence and the Trader License; and these two were further divided into two licenses each. The Refinery License and Export License were moved from MinComm to Goldbod. Till any information on the scope is provided, we would presume the Export Partnership License is the same as the Export License as previously issued by MinComm.

The Storage License, Transportation License, and Fabrication License were moved from the Ghana Police Service to Goldbod. Smelting License is an entirely new license category which was in the previous regime captured within the scope of other licenses. Importation and Transshipment Licenses did not exist before either. Again, it is not obvious that a larger number of licenses would lead to better rationalization, greater efficiency, or more compliance. Let time be the judge.

Conclusion

There are obvious and significant differences between the pre-Goldbod era and the Goldbod era; structure, mandate, licensing regime, among other factors. Stakeholders within and outside Ghana must be cognizant of the changes so they can properly position themselves; not necessarily to oppose, but to thrive within the changing policy ecosystem.